In the digital age, the pervasive influence of online platforms has raised significant ethical concerns, particularly regarding the distinction between manipulation and persuasion. As these platforms become increasingly integrated into everyday life, their ability to shape and direct user behavior has grown remarkably powerful. At the heart of this issue lies a fundamental question: To what extent does the design of these platforms respect or undermine the autonomy of their users? The difference between persuasion and manipulation is not merely academic; it goes to the core of how users interact with technology and the degree to which their choices are genuinely their own.

The Nature of Persuasion in Digital Design

Persuasion, when ethically applied, operates within the boundaries of respect for individual autonomy. It involves encouraging users to engage in behaviors that align with their interests or well-being, often by providing them with relevant information, incentives, or reminders. For example, a fitness application that prompts users to exercise by offering daily motivational tips or reminders is engaging in a form of persuasion that acknowledges and supports the user’s goals. The user, in this scenario, retains full control over their decision-making process, choosing to act on the platform’s suggestions based on a clear understanding of their own objectives.

What makes persuasion ethically defensible is its transparency and its alignment with the user’s own values and intentions. When a digital platform uses persuasion, it does so in a way that seeks to guide rather than coerce, nudging users towards choices that they are likely to perceive as beneficial or desirable. In these cases, the persuasive elements of the platform serve to enhance the user’s ability to achieve their goals, reinforcing their autonomy rather than diminishing it.

Manipulation: The Subtle Erosion of Autonomy

Manipulation, on the other hand, represents a more insidious form of influence, one that operates by exploiting users’ cognitive biases, emotional vulnerabilities, or lack of awareness. Unlike persuasion, manipulation often involves steering users toward decisions that serve the interests of the platform rather than the users themselves. This distinction is crucial because it highlights how manipulation can subtly erode autonomy, leading users to take actions that they might not fully understand or intend.

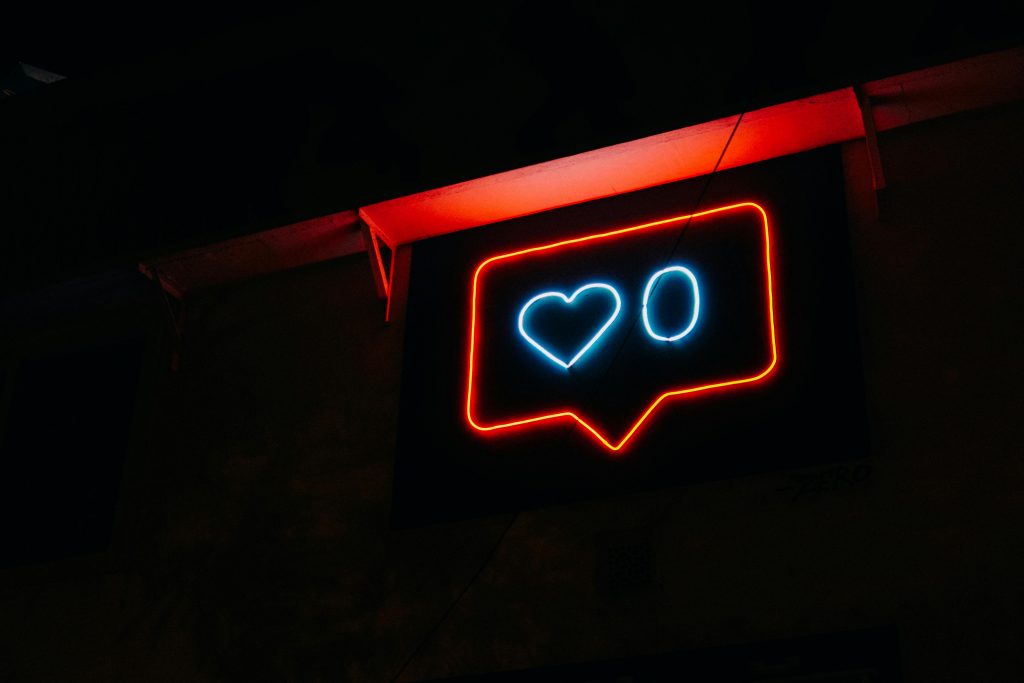

A quintessential example of manipulation in online platforms is the use of variable rewards. This tactic, rooted in behavioral psychology, exploits the human tendency to seek out rewards that are unpredictable in their occurrence. Social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook employ variable rewards by delivering notifications about likes, comments, or other interactions at irregular intervals. This unpredictability taps into the brain’s dopamine-driven reward system, creating a cycle of anticipation and reward that can be highly addictive. Users may find themselves repeatedly checking their devices, not because they have a conscious desire to do so, but because their behavior has been conditioned by the platform’s design.

What makes this form of manipulation particularly concerning is its subtlety. Users are often unaware of the extent to which their behavior is being shaped by these hidden mechanisms. Unlike overt persuasion, which presents users with clear options and encourages them to make informed choices, manipulation often bypasses the user’s rational decision-making processes. It exploits unconscious drives and biases, leading users to act in ways that are not fully aligned with their informed intentions. This erosion of autonomy is not just a theoretical concern; it has tangible effects on how individuals engage with technology and the degree to which they can control their own behavior.

The Ethical Consequences of Manipulation

The ethical consequences of manipulation in online platforms are profound. By undermining autonomy, manipulation raises questions about the moral responsibility of the entities that design and deploy these platforms. When users are manipulated into behaviors that primarily benefit the platform—such as spending more time on the site, making impulsive purchases, or sharing personal data—their ability to act as autonomous agents is compromised. They are no longer fully in control of their choices; instead, they are being subtly guided by design elements that they may not even recognize as manipulative.

This erosion of autonomy is particularly problematic in a digital environment where users are often bombarded with choices and information. The sheer volume of content and the speed at which it is presented can overwhelm users, making it difficult for them to process information critically or to recognize when they are being manipulated. In this context, manipulation can lead to a range of negative outcomes, from the trivial—such as wasting time on unnecessary content—to the serious, such as compromising privacy or making poor financial decisions.

Moreover, the manipulation inherent in many online platforms is often compounded by the power imbalance between the platform and the user. Online platforms possess vast amounts of data about their users, including detailed insights into their behavior, preferences, and psychological profiles. This data allows platforms to tailor their manipulative strategies with a high degree of precision, making it even more challenging for users to resist or even recognize the influence being exerted on them. This power imbalance further diminishes autonomy, as users are subjected to sophisticated techniques designed to shape their behavior in ways that serve the platform’s goals.

Manipulation at Scale: The Case of Social Media

Social media platforms exemplify the large-scale application of manipulative techniques, where algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement by exploiting psychological triggers. These platforms are engineered to prioritize content that evokes strong emotional responses, whether it be joy, anger, fear, or excitement. By continuously presenting users with emotionally charged content, social media platforms can keep users engaged for extended periods, often without them fully realizing the extent to which their emotions and behaviors are being manipulated.

The ethical implications of this manipulation are significant not only for individual autonomy but also for society at large. When users are manipulated en masse, the effects can ripple through communities, shaping public discourse, influencing political opinions, and even affecting mental health on a broad scale. The manipulation of content to maximize engagement can lead to the spread of misinformation, the polarization of opinions, and the amplification of extreme viewpoints, all of which can have destabilizing effects on social cohesion.

At an individual level, the constant exposure to manipulated content can contribute to feelings of anxiety, inadequacy, and loneliness, as users compare their lives to the idealized images presented by others or become entrapped in cycles of negative emotional engagement. The cumulative effect of this manipulation is a gradual but significant erosion of users’ ability to make independent, informed decisions about how they engage with these platforms.

The Ethical Dilemma of Autonomy in the Digital Age

The distinction between manipulation and persuasion in online platforms is not merely a matter of semantics; it strikes at the heart of ethical concerns surrounding the use of technology in shaping human behavior. While persuasion respects the user’s autonomy by encouraging them to make choices aligned with their own goals and values, manipulation undermines this autonomy by steering users toward decisions that primarily benefit the platform. The subtlety and pervasiveness of manipulation in online platforms pose significant ethical challenges, particularly in a context where users are often unaware of the forces influencing their behavior.

As online platforms continue to expand their reach and influence, the erosion of autonomy caused by manipulative design practices raises critical questions about the moral responsibility of these platforms. The power they wield to shape behavior, often without users’ full awareness, suggests a need for deeper ethical scrutiny and a reevaluation of the boundaries between influence and coercion in the digital age. In this increasingly complex landscape, understanding the difference between manipulation and persuasion is crucial to safeguarding user autonomy and ensuring that technology serves to empower rather than control.